Stories from Shadowbrook’s Past: Tracing the Imprints that Remain

In my journaling workshops at Kripalu, I’m often moved by the candid words I hear from guests, by their willingness to share their tales. My own perspective becomes more expansive; I receive other points of view.

I’m drawn to historical figures for this reason. After teaching class, I like to walk the Kripalu grounds and contemplate the rich stories of this land.

The Sugar Maple Path leads me through a shaded portion of woods, along the expanse of Gould Meadows, past the crumbling gatehouse, and to the old bones of the Shadowbrook mansion. As I walk, I’m accompanied by friendly ghosts.

Nathaniel Hawthorne is one. He walked these woods in 1850, soon after the publication of The Scarlet Letter, one of the first mass-produced books. Hawthorne referenced politicians from Salem in his novel, and their response was not favorable. To escape the hoopla, the Hawthornes moved from Salem to Lenox and inhabited the Little Red House, just a quarter of a mile from Kripalu. The Boston Symphony Orchestra uses a reconstructed version, now called Hawthorne Cottage, for practice rooms in summer months.

The Hawthornes stayed in the Red House for 18 months, a productive time for Nathaniel. There he finished The Wonder Book and The House of the Seven Gables and began Tanglewood Tales. He also found time to walk two miles daily to Lenox to get his mail. I see him walking slowly, hands behind his back, glad to be away from the knot of sentences to unravel. Perhaps he thought of his young friend Herman Melville, who lived in Pittsfield on a farm called Arrowhead, and had just begun writing a book about a whale.

On one excursion, the story goes, Hawthorne followed a small stream and named it Shadow Brook. (He’s credited with naming Tanglewood, too.) Is it the same stream I cross during my walk? I don’t know for sure, but I’m heartened by the possibility. My own words seem inconsequential at times, but it’s good to remember that words can sometimes stick.

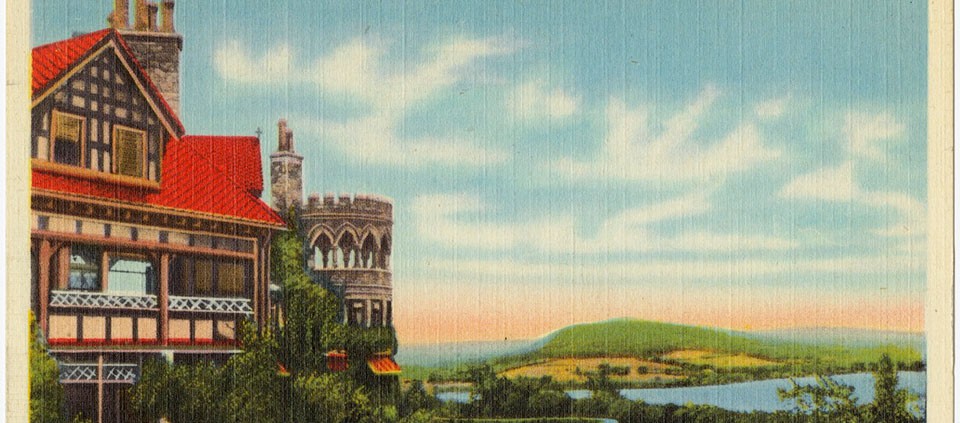

I continue along the Sugar Maple Path to the stone steps of the original Shadowbrook building. These ruins, pieces of a long-ago puzzle, fascinate me. In the space that is now the empty Mansion Lawn, I conjure up Gilded Age cottagers arriving in their carriages, greeted by a row of servants, a la Downton Abbey. The mansion, built in 1893 by Anson Phelps Stokes, had 100 rooms and a ballroom large enough for Anson Jr. to ride his bicycle indoors. I imagine the three towers, the gabled English Tudor exterior, the unimpeded view of the lake I’ve seen in photographs.

When the Stokes family left in 1898, the building remained a retreat for “cottagers,” such as Margaret Emerson, aka Margaret Emerson McKim Vanderbilt Baker Amory. She was called Mrs. Vanderbilt when she rented the Shadowbrook estate in 1915. Her husband, Alfred G. Vanderbilt, had recently died aboard the Lusitania.

What did she feel, walking in and out of 100 empty rooms? Some degree of peace, I hope. Her two young sons could be away from the busyness of New York City for a time. She could stand at the top of the tallest stone tower and look out over a mostly quiet landscape. Perhaps, in winter, she watched the snow as I do, falling softly into the black of the lake—salt shaken into the Bowl.

For steel tycoon and philanthropist Andrew Carnegie, who purchased the estate in 1917, Shadowbrook was also a place of contemplation. Carnegie had invested a great deal of money and hope in the Carnegie Endowment for International Peace, and believed that the end of war was “as certain to come, and come soon, as day follows night.” World War I was a shock to him. But he found the Berkshire Hills soothing, as they reminded him of his native Scotland—the stillness, the damp earth. The trees have grown so tall since then.

When the Jesuits acquired the building in 1922, the ballroom became a chapel and the bedrooms became dormitories and classrooms for 150 would-be priests. “Generations of novices peeled potatoes on the first floor porch adjacent to the kitchen,” writes F. X. Shea in his recollections of the seminary. “The lake valley is spacious—its length is some 15 miles—but its grandeur is quiet, modest and enclosed.” When a fire destroyed Shadowbrook in 1956, four men lost their lives. It’s said that the flames could be seen from towns several miles away. But the Jesuits stayed on to rebuild just beyond the original site.

From here, I make my way back to the new Shadowbrook building. On the terrace is a simple stone plaque, with a year engraved on it: 1957, to mark the reconstruction. The building’s next stage of evolution began in 1983, when Kripalu arrived in the Berkshires. In 2010, Shadowbrook became a place of refuge for me, too. I moved from New York City to serve as a Kripalu volunteer and never left.

Before heading inside, I turn to take in the Bowl, first called Lake Mahkeenac by the earliest inhabitants of this area. Long before the Hawthornes, Stokes, Vanderbilts, Carnegies, Jesuits and yogis, the Munsie tribe named this water. Mahkeenac means “great pond.”

The Munsie tribe continues to enrich the land. Tribe elders recently renamed the island in the lake, a 2.5-acre stretch of earth that, for generations, was known simply as “the island.” Now it is called Kwamkiikwat (“appearing long”). A sign is being created, and tribe members will join Kripalu staff next summer for the official installation and dedication, says Kevin “Moose” Foran, Kripalu Grounds Supervisor.

I often feel the impact of accumulated experiences when I am at Kripalu. When you enter a room after a yoga class, you can feel the efforts of those in the room before you. Step outside, and the same imprints exist. When I recognize their presence, I can see beyond my narrow focus, my own time and circumstances, and forge a stronger connection to other voices.

Lara Tupper walks, teaches writes, and sings in the Berkshires. laratupper.com

© Kripalu Center for Yoga & Health. All rights reserved. To request permission to reprint, please email editor@kripalu.org.

Lara Tupper, MFA, is the author of two novels, Off Island and A Thousand and One Nights, and Amphibians, a linked short story collection forthcoming in 2021.

Full Bio and Programs